The 1998 Kentucky Bourbon Festival!

My first trip to Kentucky for the Bourbon Festival took place in

September of 1998. I drove out, solo, and stayed with people I'd worked

with when I was a librarian at Ft. Knox, back in 1986. I've decided to

edit this as lightly as possible, and my ignorance may amuse you, but it

is what it is. Enjoy.

I drove to Kentucky.

Sounds easy, but from Philadelphia, it was a 12-hour drive. Yowch! But it was worth it. I was

completely mobile as soon as I got there, and I used that to visit five distilleries in three days. Admittedly, I was working under

ethics rules (imposed by the markets to which I sold stories on the festival) that made it

impossible for me to accept sponsorship from a distillery as a number of other writers at the Festival had; they were

flown in, put up in nice motels, and chauffeured about--to the distilleries approved by their

sponsors [as I would be in about five years' time!]. I paid for it myself on the cheap.

I drove, packed box lunches, stayed with old friends in the

area, and got to go anywhere I wanted. I drove to Kentucky.

Sounds easy, but from Philadelphia, it was a 12-hour drive. Yowch! But it was worth it. I was

completely mobile as soon as I got there, and I used that to visit five distilleries in three days. Admittedly, I was working under

ethics rules (imposed by the markets to which I sold stories on the festival) that made it

impossible for me to accept sponsorship from a distillery as a number of other writers at the Festival had; they were

flown in, put up in nice motels, and chauffeured about--to the distilleries approved by their

sponsors [as I would be in about five years' time!]. I paid for it myself on the cheap.

I drove, packed box lunches, stayed with old friends in the

area, and got to go anywhere I wanted.

You never know what you'll find in West Virginia..

|

The first place I went was Lawrenceburg, to visit the Wild Turkey Distillery. I was taken around on a tour by

Master Distiller Jimmy Russell. That's not actually as 'insider' as it sounds; Jimmy makes a habit of taking

two or three tours of visitors around each week. He believe it's

time well-spent to get to hear what the customers have to say about his whiskey. So if you do go and you get a

tall, older gentleman with shoulders like a linebacker... well, all I can say is to

listen closely and ask all the questions you can think of!

That's what I did. Jimmy took me through the whole distilling process

on a beautiful little model they had in the visitor's center, and this is as good a time as any to explain that here. Why don't you

pull up a stump and sit a spell while I relate it to you...

The Bourbon Story

Bourbon follows certain rules, legal and esthetic. Legally, bourbon whiskey must be distilled in America

(not necessarily in Kentucky, as many people believe); it must be distilled from a grainbill which is

at least 51% corn; it must come off the still at a proof no higher than

160; and it must be aged in new, charred, white oak barrels at an

initial proof of no more than 125. That's the

technicals. Here's how it happens.

The distiller takes his corn and cooks it hot and hard. Then as the temperature drops, he adds the first of his

'small grains,' usually rye, but sometimes wheat (Maker's Mark is the best known of the

'wheated whiskies.'). Finally, with a second temperature drop, malted barley

is added to the mash. The enzymatic power of the malt is magically clear in this process:

as it is added, the thick, porridge-like mass of corn and rye starches

swiftly becomes a much thinner soup of sugars. A certain amount of

'backset' is added as well, mash from the previous batch. This is the

'sour mash' which you have probably heard of. As I understand

it, backset is all about pH levels. Mostly, it works, so they

keep doing it.

After the mash is cooked and cooled, it goes to the fermenters and the yeast is added.

How that yeast is cultured is one of the

deep secrets of the industry. For years, Jimmy Russell was the only man

who did it at Wild Turkey; as he has gotten older, he has taken on a few apprentices who are

allowed to watch. There are a couple different ways to do it, all apparently wrapped in superstition. After the mash is cooked and cooled, it goes to the fermenters and the yeast is added.

How that yeast is cultured is one of the

deep secrets of the industry. For years, Jimmy Russell was the only man

who did it at Wild Turkey; as he has gotten older, he has taken on a few apprentices who are

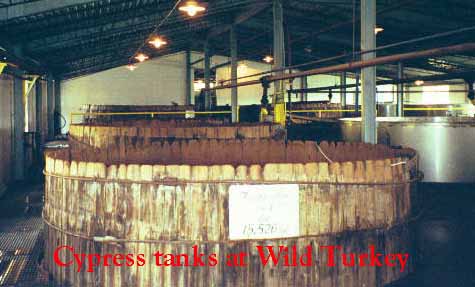

allowed to watch. There are a couple different ways to do it, all apparently wrapped in superstition.You may have noticed that I said the mash goes to the fermenters.

Unlike beer or Scotch, bourbon distillers never filter the 'wort' out of the

mash. The fermenters are filled with a murky, soupy bubbling mess that looks like the

top of a very active swamp. This is all open fermentation, ranging from the aging cypress-wood tanks still used by some distillers

(slowly being replaced by stainless steel -- "We tested that first steel tank for 9 years

before we used any of the beer from it," Jimmy Russell told me) to the cavernous steel vats

used by big distillers like Ancient Age (those were so big they were almost scary

to look into; they echoed).

When fermentation is complete, usually in 72 to 96 hours, the mash, now at about a 7.0% ABV level, is pumped to the 'beer still.' This is a

continuous, or column still, a tall cylinder with perforated plates

at about 3 foot intervals. The mash flows in the top, live steam flows in the

bottom. As the mash flows downward, the steam percolates upward

through it, heating it and carrying the vaporized alcohol with it. This alcohol is

heavy with congeners, esters, fusels... higher alchols and other compounds that give the whiskey its

distinctive flavor. As the vapor flows out the top, it is routed to either a

condenser to be liquified for a run through a second still called a

'doubler,' or as vapor through a primitive kind of still called a 'thumper' (named for the distinctive noise the vapor makes as it bubbles through the water in the thumper).

The raw distillate comes off the still at somewhere between 125 and 158 proof, depending on the distillery. At this point, it is

viciously 'hot' with alcohol, somewhat sweet from its corn base, and clear as water:

white lightning. The spirit is loaded into the charred oak barrels and trundled off to the warehouses. As Jimmy's son Eddie said,

"Four days from grains to barrel, then we put it away for years." A day's run will

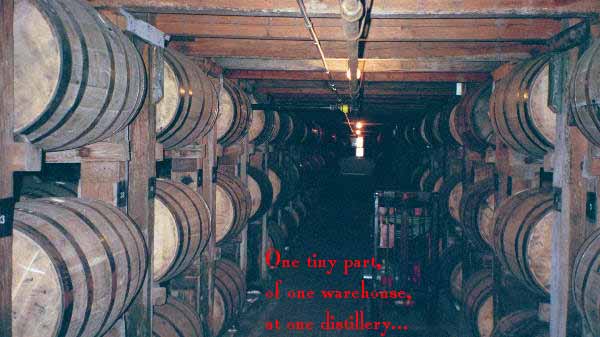

not all be put in the same warehouse; it is spread throughout a large number.

Each part of each warehouse will produce a slightly different

whiskey; each barrel will have a different effect on the whiskey.

This is where the job of people like Jimmy Russell, or Ancient Age's Elmer T. Lee and Gary

Gayheart, or Jim Beam's Booker Noe, or Barton's Bill Friel becomes crucial. These men have the years of experience and the 'photographic' memory for

taste and barrel location that will enable them to know which barrels,

when 'dumped' and mingled, will produce the remarkably consistent flavor and aroma and

'mouthfeel' profile of their whiskies. They sample barrels two or three times a week,

looking for the ones that are 'ripe,' that are coming along, and for the prized

'honey barrels' that through some mysterious alchemy are producing the very finest whiskey.

What happens in the barrels? Over the seasons, as the temperature rises and falls in the

largely unheated warehouses ("We're climate-controlled," Jimmy likes to say; "When it gets hot,

we open the windows."), the whiskey expands and contracts. As it expands, it

pushes out into the char on the wood, and beyond into what's called the 'red layer,'

a band of caramelized sugars and vanilla-like flavors in the oak caused by the heat of the charring process.

This is where the whiskey gains its familiar amber color and the

sweet, vanilla-caramel tones prized by bourbon lovers.

What's left after the wait is finally over? The dump trough. Barrels are rolled over this false-bottomed trough, the bungs are pulled, and

hundreds of gallons of Kentucky's finest gush out of the barrel, bearing chunks of char with them. The char is

screened out, then filtered out, and the whiskey goes to the packaging facility. It is filtered again (most distilleries use

chill-filtering to remove long-chain proteins that can cause an unattractive but tasteless haze in chilled whiskey), then sent to the bottling line. The bottles are boxed up, sent to the warehouse,

then to your local store, and await your inspection even as you read this!

Meanwhile, Back at Wild Turkey

Jimmy showed me the still, but it wasn't working. He just doesn't believe in distilling during hot weather. So during about 11 weeks from

July 4th to late September, Wild Turkey concentrates on maintenance and, of course, the

aging whiskey in the warehouses. That's where we went next. As we walked through the door a

pleasant wave of whiskey aroma surrounded me, and I breathed deeply. "There it is,"

I said happily, and Jimmy said "What?"

"The whiskey smell," I said, "I finally smell whiskey." Jimmy grinned. "We don't even smell it anymore," he said, and after 44 years at Wild Turkey,

he probably doesn't. Then he said "If I come in here in the morning and I do smell

something, it means something's wrong, and I go find it!"

The 22 warehouses at Wild Turkey hold about 20,000 barrels each. That's about 23,000,000 gallons of whiskey, and Wild Turkey is considered a medium-sized distillery. Imagine

all the money tied up in those warehouses!

After the Fire

When I finally said good-bye to Jimmy, I had just enough time to take care of some personal business

(getting fitted for my tux in Elizabethtown) before heading to Bardstown for the press reception at

Heaven Hill Distillery. Heaven Hill is moving in a strange

area. They had a disastrous fire in 1996. It started in one warehouse

and soon consumed four others--and the distillery

itself. So.... where's the whiskey coming from? Well, the dump house and packaging line were running full tilt

when we toured them, so there's spirits coming from somewhere.

I was told by one person that Heaven Hill was distilling at

Beam, by another that they were doing it at Brown-Forman. There is certainly plenty--plenty--of

excess capacity in this industry, and as everyone mentioned, on the production side of the industry,

everyone gets along well and there's lots of cooperation.

Heaven Hill president Max Shapira addressed this at the Bourbon Heritage Panel

discussion on Thursday at the festival. "You know, this is a very strange

industry. We may fight tooth and nail over the last 200 ml bottle sale in God knows where, but

on the production end we really work together. Prohibition forced us to co-operate, and

we never forgot that. If one of us gets a new piece of machinery we won't hide it for a competitive advantage,

we'll probably call up somebody else and say 'Hey, we got some new

machinery, why don't you come over and take a look!'" Shapira's further comment

that there were not really any poor-quality bourbons being produced

was amplified by Chris Morris of Brown-Forman, who pointed out that all the distilleries make great bourbons, just different in a number of ways. When he was asked

what made those differences, he replied "There's not one thing that

makes a whiskey what it is. It's the combination of factors that come together." It truly is a business of tiny degrees that make big differences.

But enough serious stuff. When we finished the tour, we were treated to our first taste

of the flood of whiskey that marks this festival. Imagine: 40 different

whiskeys, poured by attentive, attractive bartenders, as many and as often as you like.

It took everything I had to stay sufficiently sober to drive the 30 miles back to my friend's house (but I did: like I always say,

I'm a professional, please don't try this at home!). Because after we sipped and

sampled, they loaded us on a bus and it was off to "My Old Kentucky Dinner Train"

for dinner in a classic dining car. I didn't see much of the countryside, though: the train riders were

remarkably convivial company, and we talked for three hours over prime rib, chocolate, coffee, and more

whiskey. Finally I drove off, exhausted.

Down in the Holler...

I had to leave before dawn the next day. Toughest morning of the week! It was

almost worth it to see the sun come up over the hills and light the

mist. As I drove the deep-cut road across the southern end of Ft. Knox a

coyote ran across in front of me so close I could hear

the klikkiketyklikk of his blunt claws on the asphalt. A quick jog north on I-65, then back onto two-lane again past the

Old Mr. Boston bottling facility and Jim Beam's Boston distilling-warehousing facility (Boston, Kentucky, is an eye-blink town along Rt. 62). Then a

long run on the Blue Grass Parkway took me to Versailles, where I watched carefully for the turnoff for Grass Springs Road. I caught it and headed back to

Labrot & Graham [now known as Woodford Reserve].

Labrot & Graham is the site of one of the oldest standing distilleries in Kentucky, dating back to 1812. It operated for a while as the

Oscar Pepper Distillery, and was the place where the Scottish doctor James Crow

-- "Old Crow" -- put the distilling of bourbon on a scientific

basis. Then Messrs. Labrot & Graham bought it, and ran it through the

1940s. After it finally closed, it sat for years, unpreserved and unwanted.

Then in the 1990s, Brown-Forman decided to refurbish the distillery as a showpiece, using

pot stills to make old fashioned bourbon. They sank a ton of money into the place

("Payback on this place is in double-digits [years]," general manager Bill Creason told me, "but in

intangibles, Brown-Forman has made it back already.") and current plant manager

Dave Scheurich almost literally lived at the distillery for two

years. (He lives just down the road now, in a house that Brown-Forman moved three

times... but that's another story.) Dave, like a number of the

distillers, is a funny guy, but he's funny in a different way;

quirky, self-effacingly goofy, a more 90s distillery guy. We had a good time.

of the north fork of Glenns Creek, the bourbon equivalent of Scotch's River

Spey. Brown-Forman has built a large stone building on the shoulder of the hollow to

house a bourbon museum. Not a Labrot & Graham or Brown-Forman museum, a bourbon museum. It's not the

same kind of museum as the better-known Oscar Getz Museum in Bardstown;

it's equally appealing in a different way. This is almost more like a science museum dedicated to the science of bourbon. of the north fork of Glenns Creek, the bourbon equivalent of Scotch's River

Spey. Brown-Forman has built a large stone building on the shoulder of the hollow to

house a bourbon museum. Not a Labrot & Graham or Brown-Forman museum, a bourbon museum. It's not the

same kind of museum as the better-known Oscar Getz Museum in Bardstown;

it's equally appealing in a different way. This is almost more like a science museum dedicated to the science of bourbon.

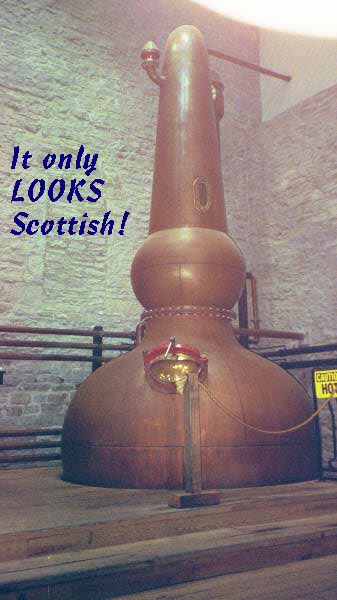

Of course, the real attraction is down by the stream. Labrot & Graham is currently the

only pot still bourbon distillery in the world. The three stills were imported from Scotland. Outside of Ireland, only one other whisky in the world is triple-distilled:

Auchentoshan, the Lowlands malt.

The spirit at L&G comes off the final distillation at around 157 proof. I

sampled the stuff: Wow! It had all the subtlety of a sharp stick in the eye

and the wonderful mouthfeel of a shot of novocaine. The corn was a faint sweetness and graininess, but it was real hard to get past that

WHAM of alcohol. I finally got Dave cornered at the Gala Saturday night and asked him why L&G's Woodford Reserve

would still taste full and rich with such a high distillation proof... but I'm afraid that I

don't recall the answer, I guess I had too much bourbon in my ear. Shoulda taken my recorder to the ball!

Anyway, the warehouses are masonry-walled and picturesque, the bottling line is labor-intensive, and it's a long way back up that hill! There is one thing to explain, of course:

the Woodford Reserve that's on the market now, delicious though it is,

was not distilled at Labrot & Graham. It was blended from select barrels of Old

Forester, and the stocks currently maturing at L&G are aiming at that flavor profile. Is this

sneaky, underhanded, or deceptive? I would urge anyone who is

struggling with these issues to do one thing: taste this whiskey. I guarantee

you won't care how it got in that bottle, so long as you get to drink it! What's more, Chris Morris of Brown-Forman promises that "magical whiskies will be coming from Labrot & Graham."

Don't even believe that Woodford Reserve will be the only product.

Big. REAL BIG.

I hopped back in my car and tooled down the road into Frankfort. I was going to one of the

big ones, after having toured two of the smaller ones: Ancient Age, also known as the Leestown

Distillery [and now known as Buffalo Trace]. Until I 'discovered' bourbon three years ago,

I'd never heard of Ancient Age. BTW, I feel no shame in my ignorance regarding bourbon at all any more.

At least a dozen people asked me if I got any Jack Daniel's at the Festival; JD is

Tennessee Whiskey, not bourbon, and it's distilled in (duh!) Tennessee!

Ancient Age is the distiller of the first 'small-batch' bourbon, Blanton's. [Though

Jim Beam actually came up with the term.] Ancient Age now makes five of these select whiskies:

Blanton's, Benchmark, Elmer T. Lee's (named for Ancient Age's Master Distiller

Emeritus), Rock Hill Farm, and Hancock Reserve. Each of these whiskies is

distinctly different, and yet... Each is distilled and fermented in exactly the same

way. Huh?

It's all in the barrel! The importance of the aging process in bourbon-making

CANNOT be overemphasized. The distillate is raw, hot spirit. It becomes whiskey in those barrels. And the

barrels vary by grain of wood and size of stave, the warehouses vary

by construction and placement, and there is a great difference in some warehouses

between high and low position, outer and center position. Jimmy Russell

famously won't put barrels on the third level rick on the east side of the first floor of his front warehouse at Wild Turkey, says the

whiskey won't get good there. Look, the man's been doing it for 44

years: are you going to argue with him?

Elmer T. Lee favors one warehouse at Ancient Age, the Master Distiller, Gary

Gayheart, favors another. The barrels they choose from these warehouses taste

different, and they can consistently find barrels to match the profiles

they've created for these five whiskies. How do they do it? How did

Van Gogh choose the blues for "Starry Night"? How does Miles Davis pick his next note? Picking barrels is an

art, and that is why these men are called Master Distillers. I learned

tremendous respect for their palates over these four days.

It's all in the barrel! The importance of the aging process in bourbon-making

CANNOT be overemphasized. The distillate is raw, hot spirit. It becomes whiskey in those barrels. And the

barrels vary by grain of wood and size of stave, the warehouses vary

by construction and placement, and there is a great difference in some warehouses

between high and low position, outer and center position. Jimmy Russell

famously won't put barrels on the third level rick on the east side of the first floor of his front warehouse at Wild Turkey, says the

whiskey won't get good there. Look, the man's been doing it for 44

years: are you going to argue with him?

Elmer T. Lee favors one warehouse at Ancient Age, the Master Distiller, Gary

Gayheart, favors another. The barrels they choose from these warehouses taste

different, and they can consistently find barrels to match the profiles

they've created for these five whiskies. How do they do it? How did

Van Gogh choose the blues for "Starry Night"? How does Miles Davis pick his next note? Picking barrels is an

art, and that is why these men are called Master Distillers. I learned

tremendous respect for their palates over these four days.

Ancient Age marketing fellah Chris McCrory took me around this big place. It was

strange to be wandering around a distillery this big (Ancient Age is rated at

10 million gallons a year capacity) that was so underutilized. They were in the midst of a distilling holiday brought on by the hot weather. Bottling and warehouse operations continued full speed, but distillation was in maintenance mode.

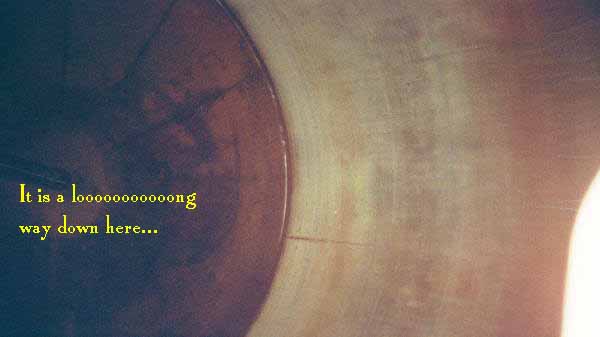

Ferment tanks at Ancient Age: about 92,000 gallons each. This is one of twelve. |  |

We looked in on the fermentation tanks; they were disturbingly deep, and made me somewhat nervous to be around. If I somehow had

fallen in, I'd have broken lots of bones when I finally hit bottom. Guess I'm not afraid of heights, I'm afraid of depths!

Anyway, then Chris led on to the yeast propagation room (unused: it was built to supply multiple distilleries in the area, and is

too big to run now), the big column still, the packaging room, and finally the

warehouses. As we strolled into the warehouse we saw the line of barrels

you see two pictures above, all stamped "BLANTON BOURBON selected by master distiller ELMER T. LEE."

Joe Congiusti, the whiskey man from the esteemed Sam's Wines and Spirits of Chicago, was down tasting barrels of Blanton's.

[Joe later worked for Binny's, and sadly died way too young last year.] He was going to select

one barrel, which would then be taken to the special Blanton's dump room and bottled, about

250 bottles which would then have a sticker put on the back noting that this whiskey was

specially selected for Sam's customers. I watched a bit, but didn't want to intrude.

Last we made our way up to the tasting room. We sat down with copita glasses and nosed and tasted part of the range of whiskies:

Ancient Age, Ancient Ancient Age 10 Star, Blanton's, Elmer T. Lee's, and Ancient Ancient Age 10 year

old. I have to say, for the money, Ancient Ancient Age 10 year old may be the

best value on the market. The bang for the buck -- this is a damn good whiskey that sells for around $12.50 a bottle -- is hard to beat.

It's a damn shame it's sold only in Kentucky!

Eggs of a Stupid Fish

I thanked Chris for his time and headed on down the road. After picking up my tux for the

Saturday night gala and calling home, I caught my first official Festival

event; the Jim Beam-sponsored "Culinary Arts, Bourbon Style" cooking demo with chef

Jim Gerhardt of The Oakroom restaurant at Louisville's Seelbach

Hotel. It was just like being in the audience at a cooking show -- except for the welcome presence of

Seelbach 'Emeritus Bartender' Max Allen and pitchers of his fabulous Bourbon Manhattans. Cheers, baby:

I was never much for Manhattans, but Max made a believer of me. Here's the secret recipe:

2.5 oz. Bourbon (don't stint on the quality)

1/2 oz. Sweet Vermouth

1 dash EACH Angostura and Peychaud Bitters

1 splash Grenadine

Shake with ice and strain into a chilled cocktail glass, garnish with one perfect maraschino cherry.

Yes, I know Peychaud Bitters are hard to find. But that's what makes this Manhattan so great, so find some!

The cool thing about Jim Gerhardt is that he has pulled everything he can find out of

the region and incorporated it into his menu. We ate red bliss potatoes

garnished with caviar from spoonfish, a local cousin of the sturgeon that Jim said was

a pretty dumb fish; "Any more docile and they'd jump into the boat for you." Delicious, clean,

bursts of flavor, I was real happy with them. We had beef tenderloin

marinated overnight in bourbon, a salad of Bibb lettuce grown in KY limestone soil (Jim swore it made a difference), and

chicken stuffed with Country Ham -- don't think of the country ham as that

wooden stuff sold at Cracker Barrels, think of paper-thin slices of prosciutto

and you've got it. There were also cheese corn cakes made with Kentucky's Trappist cheese,

Gethsemani. Dessert was buttermilk biscuits with bourbon-marinated berries and bourbon-laced whipped

cream. Small portions were the rule of the night -- only I hung around and

swapped lies with Max and tore into leftover biscuits and chicken, washed down with

more Manhattans. A good night!

A Visit to Tibet

Next morning was not too bad either. We had a press reception and tour at Four

Roses. Some of you older readers may remember Four Roses

bourbon, but it's been off the market for years. This is because Seagram decided to

concentrate on the export market. The only place you could get Four Roses in the U.S.

was when you were leaving the U.S. in a duty-free shop! Crazy, but it evidently worked for Seagram. However, with the

new American interest in bourbon, Four Roses is returning home. This reception was one of the first shots in the barrage of publicity, no doubt. It was

kind of strange: here was whiskey made in America that very few people in America have tasted. It's almost as if these guys had

cut themselves off from contact with the rest of the country, and now something had happened and they were

welcoming us again... but weren't quite sure how to go about it.

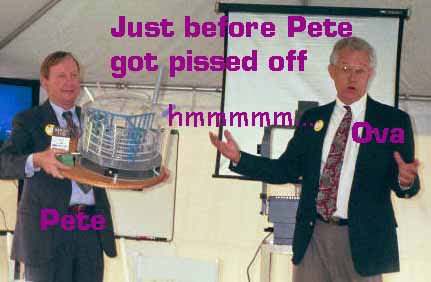

| We got an interesting talk on distilling from

Master Distiller Emeritus Ova Haney, a dryly funny country boy with a small

streak of goof in him, and Seagram honcho Pete Gunterman, who looked like the

X-Files' Smoking Man's jolly twin. He wasn't always jolly, though, in fact he got

downright surly with us a few times, like when we giggled at his

battery-powered mash cooker model. I mean, I'm sure that kind of thing

goes over big in the Japanese market (and actually, it did go over big with the

Japanese press group that was there), but we jaded American press folks

look at a grown man holding what looks like a Captain Lazer Space Station

as it faintly hums and baby-blue plastic pipes go round inside it, and our reaction is

"Oh man, how much is he getting paid?!" Then we realize how much Seagram must be paying him, and then we

look again at what he's doing and -- we giggle. |

|

Anyway, after the Ova & Pete Show (Ova did give us an excellent description

of what goes on in the beer still, condenser, and doubler, from which I took much of my description above), we all formed up for tours of the distillery. I got lucky in two ways. First, the

Czech press contingent -- and their drop-dead gorgeous interpreter -- went on my tour; second, my tour was led by

Al Young, Operations Supervisor at the distillery. Al was a real 'no-shit' kind of guy

who took us to all the important spots and answered all our questions. He

absolutely endeared himself to me as we were walking through the oppressive Kentucky heat and humidity from the grain inspection point to the still house by

suddenly blurting out "Why in the hell can't they do the Festival in

November?" Al. My man.

Anyway, the story on Four Roses is that here they blend their

bourbon. It is not a 'blended whiskey,' a mixture of whiskey and neutral grain spirits, it is a

straight bourbon blended from up to twelve different recipes of

whiskey. Four Roses does this to insure consistency in the brand. The

different recipes are a closely held secret, and it is not completely sure if

all twelve are made here at the Lawrenceburg distillery or if some might be made up at

Seagram's big Indiana distillery. Whatever they're doing, it's

working. When we finally got done with the tour I was sweating like a pig

and couldn't wait to get a big glass of whiskey. Plenty of ice, about

three logs of bourbon on the fire, and yeah! Four Roses was the

most impressive of the 80 proof bourbons I sampled that week by far. Funny note, though: as things

loosened up a bit and we started just grabbing bottles to pour our own, I

took a look at the label. About two thirds of it was in Japanese. Guess that American market intro isn't

just around the corner after all! [It wasn't, either, probably

due to the imminent sale and break-up of Seagram.]

|

After years, Four Roses is breaking their U.S. silence and returning their delicious 80 proof table whiskey to the market.

|

Jedi Bourbon Masters

After the Four Roses tour I jammed my new Four Roses cap on my head and buzzed back to Bardstown for the Bourbon Heritage Panel at the Oscar Getz Museum. This is a Festival tradition, a gathering of

six eminent people from the industry who field questions from the audience and give them their best shot. This year's panel included

Jimmy Russell, Ova Haney, Barton's Master Distiller Bill

Friel, Maker's Mark Master Distiller Emeritus Sam Cecil, Heaven Hill Distillery president

Max Shapira, and Brown-Forman's marketing maven [and now

newly trained master distiller] Chris Morris.

Things started out with a cool twist: the museum donated an excess bottle of pre-Prohibition bourbon

from the collection, distilled in 1916, bottled in 1933: 17 years in the barrel. (Bourbon distillers

generally do not like to keep their whiskey in the wood longer than 12

years, but I believe that this stems from days when 'barrel management' was

not as important as it is today.) The panel swirled, sniffed, and speculated

on how this bourbon might be different from today's whiskey. Max Shapira pointed out that there was no

hybrid corn strains available then, and that the ratios of the 'small grains' would probably be different; unfortunately, he didn't follow up on that. Bill Friel thought a

big difference would be that the whiskey probably came off the still at a lower proof than is common

today, and went into the barrel at a lower proof as well. The whiskey, unfortunately

was a disappointment. Jimmy and Bill announced that they found it to be resinous and

'aldehyde-y' (how's that for being simultaneously technical and down

home?), probably either from too long in the wood, or something wrong

with the wood itself. "Maybe a sap pocket," said Jimmy.

The give and take began. One person asked if the distillers ever did anything new

other than pulling out the small batches. (All I could think was that the last

new thing they tried before that was 'light whiskey,' so shut the hell

up!) Yes, said Max

Shapira, "there are many experiments going on all the time; for instance, with

levels of char in the barrels, and ways to increase the surface area

of the char. We did an experiment where the barrel staves were all cut like a sawtooth

(here he moved his hand through the air in a zigzag pattern) to increase the area of char

that would be in contact with the whiskey. It didn't really work out too

well." Jimmy Russell talked about a question about age statements: "It makes a

big difference when a whiskey is distilled. A whiskey distilled in November will be a

different 'year' than one distilled the following June, but the cold winter

hasn't really done much to age that November whiskey. We don't like to

barrel in the hot weather, the whiskey flows into the wood too fast."

When the Panel finished up, I ran for my car and flew over the backroads to Ft. Knox, where I

met my friends and headed up to Louisville. We went to an Outback Steakhouse,

where I had a great piece of beef and my first Kentucky Tavern

bourbon. Distilled by Bernheim and aged in Owensboro, KY,[true,

then] this is a good whiskey for the price [still true]. I also

took the waitress by the nose and led her to where she could get me an Old Australia

Stout, definitely the best beer available at this Foster's-swilling junk-beer

hell. Later we went to one friend's apartment and played cards and drank some

Ancient Ancient Age 10 Year Old and Sierra Nevada Wheat I picked up on the way. Whew! Good thing we weren't playing for money!

A Beer Interlude

The next morning, Saturday, I hustled over the river to beautiful New Albany, Indiana. Okay, actually,

IT was one of the uglier stretches of territory I'd seen in the area, but...

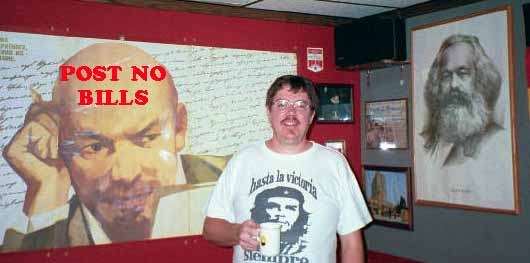

Rich O's Public House was there, where Roger Baylor holds forth with his distinct style of beer worship.

| Roger's beery theology features Augie Busch III as its fire-breathing

Devil incarnate, Arthur Guinness and Bohemian brewers as gods, and has an

odd annexed pantheon of Communist heroes, as evidenced in this picture of

Roger in The Red Room. Don't -- don't! -- get me wrong: Roger takes beer

very seriously, knows more about it than most people, even more than

most people reading this, and I dig old Communists too, as only a romantic Russian history enthusiast can, but... Roger's real passionate! Hey, it makes for a

more interesting world. [Roger has added a brewery to Rich O's

and Sportstime Pizza, the New

Albanian BC, and it's excellent, a must-stop in the area.] |

I heartily recommend Rich O's; it's worth a trip across the river from Louisville. Give them a ring for directions

if you find yourself nearby, it's

definitely worth the trek (812/949-2804).

I made tracks for Louisville's Bluegrass Brewing Company next. I'd checked out their

massively wonderful Bearded Pat's Barleywine at last year's

GABF [1997], and had heard LOTS about the place from Prodigy Beer Talk regular

Autumn Kruer, and I really wanted to drink there! It was

not a disappointment, especially since I got there before they opened

and had a good excuse to hog down a lunch of White Castle sliders

and fries!

| I got right down to business with a firmly hopped glass of Alt. Pretty soon

Autumn showed up, and we frightened the bar crowd with our loud and raucous

laughter. I could quickly see why Autumn travels an hour to get her six (!) growlers filled at

BBC: it was pretty much all really good beer!

Downside: they didn't have the Smoked Porter (dammit), and unfortunately, due to a

serious case of 'beer flu' the assistant brewmaster didn't make it in to

deliver on a promise of a vertical tasting of three years of Bearded Pat's

(double dammit). After sampling some more beers (not many: I was

conserving myself for the evening to come!), I bid Autumn a fond farewell

and climbed into the Jetta for one last run to Bardstown for the Auction, the Festival grounds, and the

Gala. |  |

SOLD! To the Japanese Gentleman...

| I hustled my butt down to Bardstown and went into the Whiskey auction.

This was mostly bottles autographed by master distillers, although Heaven Hill

put up a couple bottles of the 23-year-old whiskey they only sell in Japan (WHAT? I

consider this an outrage, but there you are). The really interesting stuff was at the end,

excess bottles of pre-Prohibition whiskey from the museum's stock. I'm told there are

thousands of pre-Pro bottles in storage... but it seems hard to believe. If there was

all that pre-Pro whiskey sitting around in 1934, why did distillers sell

2-year-old rotgut to make money?

Dunno, just reporting what I've heard. |

|

After the auction, I reached a state of panic trying to figure out

where to change into my tux. The only room I had access to was half an hour

away, and that would be cutting it mighty fine. I took a chance and called

my buddy Alan Moen, another beer guy sopping up free booze and food. Sure, come on up, he

says. That's when I discovered that the zipper on my rental tux pants didn't work.

The gizmo slid up and down okay, but the teeth didn't stay together. I was losing my mind, and the heat wasn't helping.

|

Luckily the jacket was long. Alan and his wife successfully convinced me

that unless I sat down with my jacket unbuttoned you couldn't see a

thing, so I stopped worrying and got in the car to head over. Between the fuss and the 94 degree heat I was

sweating like mad. I had the AC in the car on MAX for the whole trip, and it

helped a little. When I got to My Old Kentucky Home State Park

(yeah, really), I was feeling human again. When the parking valet took my car and I was

welcomed to The Tasting Tent, I started feeling downright good.

Whiskey! All you want!

The Tasting Tent was absolutely insane. For a $100 ticket you got the

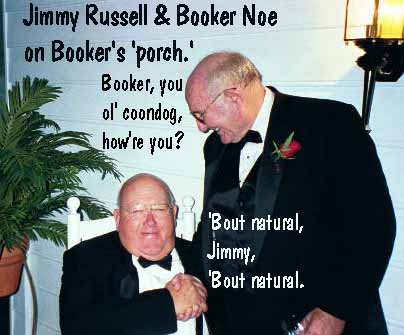

run of Kentucky's distilleries, and their personalities. There was Jimmy Russell yukking it up with

Booker Noe on Booker's 'porch' that the Jim Beam people had recreated in the tent.

Dave Scheurich was handing out classy copper shotglasses at the straw-baled Labrot & Graham booth, and

Jim Rutledge was perhaps the happiest man in the tent: he was standing right beside a

huge block of ice that Four Roses had as part of their display -- "Four Roses:

the whiskey ice was invented for." But the noisiest, busiest display

[it always is!] was Maker's Mark. They had mocked-up a

speakeasy, complete with flappers, gangsters, a ragtime piano player, and even a reporter with an old grip camera and flashbulbs. They were serving

'Big Apple Manhattans,' made with apple brandy. They were icy cold and

delicious, wonderfully welcome in the steamy tent. The Tasting Tent was absolutely insane. For a $100 ticket you got the

run of Kentucky's distilleries, and their personalities. There was Jimmy Russell yukking it up with

Booker Noe on Booker's 'porch' that the Jim Beam people had recreated in the tent.

Dave Scheurich was handing out classy copper shotglasses at the straw-baled Labrot & Graham booth, and

Jim Rutledge was perhaps the happiest man in the tent: he was standing right beside a

huge block of ice that Four Roses had as part of their display -- "Four Roses:

the whiskey ice was invented for." But the noisiest, busiest display

[it always is!] was Maker's Mark. They had mocked-up a

speakeasy, complete with flappers, gangsters, a ragtime piano player, and even a reporter with an old grip camera and flashbulbs. They were serving

'Big Apple Manhattans,' made with apple brandy. They were icy cold and

delicious, wonderfully welcome in the steamy tent. |

Me & my buddy Alan Moen, loving 4 Roses' Big Chunk O' Ice! |

I dove in. It was hard not to! I regret to admit that I had almost everything

on the rocks: it was just awfully hot. Most everyone was in tuxes and evening

gowns, and sweating freely. The whiskies that stick out were Four Roses;

Hancock's Reserve (another of Ancient Age's small batch bourbons, elegant yet

robust); Booker's (Good God, feel that barrel proof power, and taste everything an unfiltered whiskey has);

Wild Turkey Rare Breed (low barrel proof really does mean more flavor);

Woodford Reserve (again, again, again, what a fine drinking

whiskey); and Henry McKenna 10 Year Old Bottled in Bond. Did I mention

that it was open bar, all you want, and people were freely dumping

whiskey to try something else? Amazing. |

And then it was time for dinner. I settled in with Alan and his wife at one of the

'press ghetto' tables in the second tent, and had a great

dinner. Whiskey continued to flow freely, but the temperature was finally sliding downwards

a bit... or maybe I just didn't give a damn anymore. I had snagged a

fine figuerado from Mike Rubish of Pipe & Tobacco magazine, and as dinner wound to a close, I

fired that booger up, leaned back in my chair, and proceeded to swap beer-writing lies with

Alan, to the great amusement of a gorgeous woman from the KY Tourism

Bureau. It was a grand time, I had finally managed to forget my zipper problems

and appreciate the conviviality of the crowd. Wonderful people, all of

them. ("It must be the whiskey," I told my host later; she

cocked an eye at me, and said "No, it's the Kentucky." I

suspect she's right; they're awfully nice people.)

But Alan and I were getting itchy. The evening was winding down. We decided to

wheel back into town to see what was happening. Thanks to copious amounts of water

throughout the night and judicious pacing, I was not nearly as inebriated

as you would think from the above account, and we reached the Museum grounds

without incident and parked. I immediately shucked my sweat-drenched tux

for more comfortable shorts and shirt, while Alan remained dapper in his tux and Panama

hat. We soon realized that things were winding down here as well. We

grabbed one last chance at fun when we overheard some

twenty-somethings bemoaning the closing of the drinks concession. We

gathered them up, along with a handy jug of spring water and some cups,

and headed back to my car for an impromptu tasting session.

I set the cups up on the trunk of my car, and pulled out that bottle of Ancient Ancient Age 10 year

old. I poured it around, "drink up!" I called. One balked: "But this ain't

Evan Williams," he whined. Proud of his loyalty to a local brand, I

still forced him to open his horizons. "Drink it!" I commanded, and they did. Once they got over the shock,

we had a nice little drink... And then we said good night. I took Alan

back to his motel and drove back to Radcliff. The next morning, I drove

home. It was six days well spent, and

I reckon I'll be headed back next year. |