A Memory of Bert Grant

September 3-5, 1997

The 1997 Yakima Hop Harvest

On September 3-5 I traveled to Yakima, Washington

along with 11 other beer writers as the guest of Bert Grant's Ales and

Stimson Lane to witness the hop harvest. It was a long time ago, and I

was a bit more...exuberant.

Welcome to Yakima!

After some pretty smooth flights from Philly to Chicago

and then to Seattle, I met up at SEATAC airport with Tony Forder (Ale

Street News), Willi Loob (then with Beer Connoisseur, now

with Food & Wine), Stan Hieronymous (The Beer Traveler), Tom

Bedell (freelancer, great guy), and Phil Doersam (used to do Southern

Draft, not sure where he is now). We had half an hour till our

flight to Yakima, so we hit the bar for fresh taps of Redhook ESB,

Full Sail Golden Ale, and Alaskan Amber.

Fortified, we climbed on the turboprop for a beautiful hop

over the mountains. As the sun set, Mt. Rainier came rearing up out of

the billowing white clouds. Yakima was clearly a farming area, the

fields of hops and grapes and the apple orchards plain to see from

above.

Ben Myers greeted us at the airport (Ben was doing PR for

Stimson Lane at the time; he's since left the beer biz for more

remunerative work) with leis of Chinook hops (Phil guessed the hop

correctly), we picked up William Abernathy (formerly Celebrator,

last seen in Manhattan), Alan Moen (Northwest Beer News) and

Peter Terhune (formerly Ale Street News, now in advertising and

still a good friend) and we were off to Bert Grant's Pub. We took over a

big table by the (cold) fireplace and started eating (good food, but why

would you bring a bunch of men with beards a veggie and hummus plate?)

and drinking.

We got cask-conditioned Scottish Ale

(very

nice, but not quite up to the standards of East

Coast cask-conditioned stuff, I'm afraid!),

IPA (well, just what you'd expect: HOPPY!!), Perfect Porter

(sporting a LOT of vanilla from the oak-aging, a creamy mouthful),

and Imperial Stout (beefy stuff, and made a hell of a mix with the

IPA). We talked, we laughed, we drank. Around 9:30 Ben

guided us out to the bus and we went to our hotel. After we dumped

our bags, Ben got out his AmEx card and a box of cigars,

and we took over the corner of the lounge. We drank a lot more Scottish

ale and Scottish whisky and American whiskey... and then I

went to bed around 12:30 local time. 3:30 Lew's Body Time.

We got cask-conditioned Scottish Ale

(very

nice, but not quite up to the standards of East

Coast cask-conditioned stuff, I'm afraid!),

IPA (well, just what you'd expect: HOPPY!!), Perfect Porter

(sporting a LOT of vanilla from the oak-aging, a creamy mouthful),

and Imperial Stout (beefy stuff, and made a hell of a mix with the

IPA). We talked, we laughed, we drank. Around 9:30 Ben

guided us out to the bus and we went to our hotel. After we dumped

our bags, Ben got out his AmEx card and a box of cigars,

and we took over the corner of the lounge. We drank a lot more Scottish

ale and Scottish whisky and American whiskey... and then I

went to bed around 12:30 local time. 3:30 Lew's Body Time.

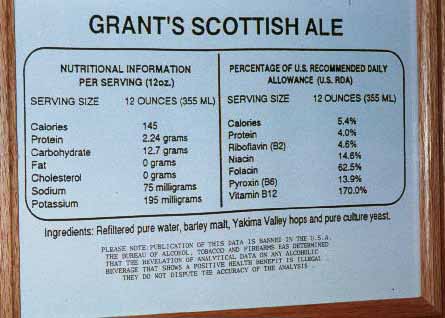

This is the 'illegal' nutrition label Bert put on his

Scottish Ale.

The BATF forced him to remove it.

Day 2: Out to the Fields

And didn't my stupid body wake me up at 5:30 local time!!

I got to have a talk with myself... After a shower and breakfast, we

loaded onto the bus for a trip to the American Hop Museum. Great

place, completely volunteer staff. Big collection of old photos of

hop-picking, tools and living equipment of the migrant workers, many

of whom were American Indians. We learned how hop-harvesting used to be

done (laboriously and slowly).

Then we sampled single hop versions of Grant's IPA, brewed

with identical IBUs of Nugget, Galena, Centennial, and Liberty. Hop

character is the single most elusive component of beer for me. I

just have problems teasing out 'grassy', 'floral', 'spicy,' and

'citrus.' This really brought it home, and I have determined to

learn this skill.

We then went off to S.S. Steiner's Golden Gate hop ranch,

where we went out to a muddy hop field, rubbed open cones in our noses,

and asked impertinent questions. They had a windstorm three weeks

ago which took out 5 or 6 'hopyards,' the heavily braced and

guyed wire/pole grids which support the hop vines. Must have been

something to see!

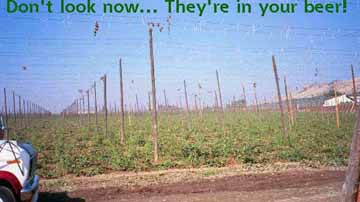

I got really weirded out by the sight of empty hopyards. There

was something hypnotic about the long symmetrical rows of poles,

marching off in straight and diagonal lines, with the wires and dangling

twine knots making a semi-opaque top cover. The effect almost had

me in a drooling stupor as we drove past these empty fields. . .

. Here, take a look:

The processing 'facility' was some buildings in a hopyard.

They bring the cut vines to the facility, hang them on hooks and

run them up a chain to be picked. The machine mostly consists of a

series of wire 'fingers' which pick the hops off the vines.

Everything falls onto a set of 'dribble belts,' constantly moving

belts which are set at a slant, partly offset from each other, something

like this: /////////, only the whole set is also angled upwards to the

right. The belts move upwards. As they move, picked hops, being

more circular, roll DOWN the belts, while hops with leaves and stems

attached move upward. The rolling and dropping also help separate

the hops from the stems. The clean hops fall through to a

conveyor belt. The leaves and stems which reach the top belt go back for

another run through the fingers. Really ripe hops come off the

vine quite easily, overly ripe ones fall apart.

Once free of leaves and stems, the river of green, redolent cones

runs across to the kiln. Here they are evenly spread (by a traveling

belt) in rectangular beds 28 to 40" deep, depending on the type of

hop. The propane burners beneath send a rush of hot air up

through slatted floors covered with thick, open-weave cloth. The hops

will take between 7 and 12 hours to dry from 80% moisture to 10%,

depending on the hop, the time of day, and the prevailing humidity.

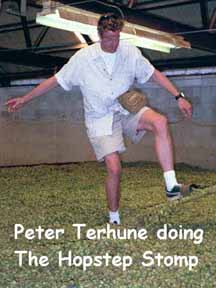

The boss of the kiln (Joe Carde

The boss of the kiln (Joe Carde

na, a

15-year veteran who learned the tricks from his dad) will put on 'the

hop shoes', two 1X2-foot slabs of thin plywood with canvas

straps [That's Peter Terhune trying them on], and walk

out onto the hop bed, turning and testing with a big 5-tined

pitchfork. His knowledge of the status of the hop is crucial:

dump too soon, and the hops have too much moisture and will be

unacceptable at the warehouse; wait too long, and the hops

will fall apart at a touch. 10% is perfect, but the hops on top

will be wetter, those on the bottom drier. The idea is to

dump them in a mixed heap to cool, and the moisture will equalize.

Then the hops are baled in 200 lb. bales, tested with the moisture

probe (NOT something you would want to be tested with

yourself, believe me), and loaded on the truck.

Why do they dry hops? Real simple: if they didn't, they

would start to rot within a day or so. In fact, hops are a

pretty sensitive crop. As I said, the wind had blown down some

hopyards. Steiner's supervisor at Golden Gate was going to shut

down operations ("These Galenas aren't coming in ripe

enough anyway.") and move his pickers to help his

neighbors get as much of that crop as possible. For a fee, of

course! But those hops had to be picked off the ground within days

or they would be ruined.

As I said, these were Galenas. The vast majority of the

Valley's hops are high-alpha hops like Galena, Nugget , Cluster,

Chinook, and a relative newcomer, Eroica. (The big aroma hops are

Willamette, Tettnang, Cascade, Mt. Hood, and Fuggles.) These are usually

used in pelletized form by major brewers, the theory being that high-alpha

hops lower costs. They are more compact (more bitter per cubic

foot), weigh less (more bitter per lb.), and cheaper (more bitter per

acre). Yakima grows 30% of the world hops crop on 32,000 acres of

hopyards. Half of the Yakima crop is exported, a of it to the big South

American and Asian brewers. As an interesting sidenote, Kevin Laurent,

the ranch supervisor, said that about 25% of the Valley's hops were

grown on land leased from local Indian tribes.

Hop Cheese, Hop Pellets, and other Unnatural Things

Then it was back on the bus, to head for Steiner's facility in

Yakima for warehousing and pelletizing operations. Did you know

that A-B uses aged hops? Steiner had a whole warehouse about 3/4

full of them. It was COLD in there, too. They were stacked up,

just sitting there. The hop buyer came close to saying he thought it

was nuts, but noted that A-B always pays on time. He also said that A-B

was fanatically picky about the quality of the hops they bought on

the open market. "Plenty of hops Busch rejected we've sold for

premium prices and the brewers were glad to get them."

Anyway, we met this buyer, Tom Huck, and a hop tester,

Jerry Patenode. Tom was the talker, Jerry was the doer.

(Funny little sidenote: the fellow who was taking us through

Steiner kept saying "This is [insert name of worker here],

who knows more about [task/hop knowledge here] than I do,

a LOT more!" At which point I'd think to myself "But

you tell him what to do!" Business is strange, isn't

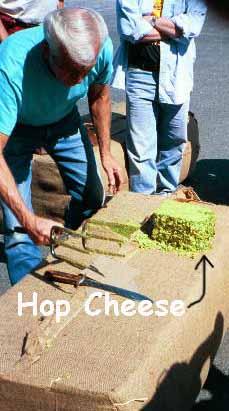

it?) Tom told us about the tools Jerry uses. There was the aforementioned

moisture probe, a small (20") harpoon-like tool

called a 'tryer', a corer, which looked like a twin-handled

punch, and a really mean looking thing that looked like a

pair of pliers made out of two short-handled pitchforks (see

photo).

Anyway, we met this buyer, Tom Huck, and a hop tester,

Jerry Patenode. Tom was the talker, Jerry was the doer.

(Funny little sidenote: the fellow who was taking us through

Steiner kept saying "This is [insert name of worker here],

who knows more about [task/hop knowledge here] than I do,

a LOT more!" At which point I'd think to myself "But

you tell him what to do!" Business is strange, isn't

it?) Tom told us about the tools Jerry uses. There was the aforementioned

moisture probe, a small (20") harpoon-like tool

called a 'tryer', a corer, which looked like a twin-handled

punch, and a really mean looking thing that looked like a

pair of pliers made out of two short-handled pitchforks (see

photo).

They went to work on a bale of Cascades with these things.

The moisture came out around 9%, a tad low. The tryer is punched

right through the burlap and retrieves a finger's-width

sample of hops. The corer requires a slit in the burlap,

which Jerry made with a runty machete which appeared to

be QUITE sharp. The corer was then forced into the bale, and

brought out a plug of hops about 10" long and

2" wide. Keep in mind that the hops are tightly compressed

in these bales. Then Jerry whacked three slits in the burlap like

this l_l and worked the fork-pliers

into the hops. He pulled out a block of compressed

Cascades about the size of 8 lbs. of stick butter (it was 2

lbs. of hops, Tom told us). He trimmed it down, and it looked

like Stilton cheese, and held together better. You could

actually pick it up, the hops are so compressed (and cohesive;

that lupulin is pretty sticky stuff.) This is what is sent

to brewers as samples of a lot.

Jerry is a pro; this is his 36th season as a hop tester.

He has gotten to the point where he can not only tell a hop

variety by smell, but by feel as well. Tom told us there

had been a mistake at one of the processing facilities, where a kiln-load

of Galenas had accidentally been dropped on a big pile of

Nugget. No one realized it until the mixed hops had already

been baled, about 200 bales. That's a LOT of hops, a LOT

of money. Jerry went through, and in about three days of work

with the tryer, picked out the bales which were Galenas

(about 46 of them), and those which had enough Galenas in them

that they could not be sold as Nuggets (about 15, I think). Tom

said that weight analysis and chemical testing bore him out on

the money. Now THAT'S knowing your hops!

Next we went to Steiner's pelletizing operation. Bert

Grant designed and built this for them back in the 70s, the first

of its kind in America. Brewers were using powdered hops for two

reasons. They were MUCH easier to store (they took up about 1/2 the room

of whole flowers), and the utilization was higher. BUT they were a

booger to use, because the powder had a tendency to blow right up

the exhaust stack when it was added. So Bert designed a mill based on

pelletized animal feeds.

The hopbales are run through a 'bale-breaker' (lots of giggles

on THAT one!), then fed to a hammermill, which crushes them to powder.

The powder is thoroughly mixed, then fed to the pellet dies,

horizontal wheels with pellet-sized holes, and the powder is crushed

into the holes by heavy rollers. The pellets hold together by the 'glue'

of the lupulin (which is heated slightly by the pressure of the

process). The pellets are bagged in barrier packages which are

pre-evacuated and flooded with either CO2 or nitrogen. The hops are said

to be good for two years in proper storage.

Frozen hop pellets? You betcha! The other pelletizing line was

the same as the first, up to the point where the hop powder went into

the mixer. At that point the hop powder entered a cold room, something

like -10F. This turns those nice soft, sticky lupulin glands into

bitter little marbles... which makes it really easy to shake out the

'leafy matter.' That's done, and then it's all shaken up a second

time, which gets even more marbles out. Then this concentrated

lupulin 'gravy' is sent to the pelletizer, resulting in a pellet

which is incredibly high in alpha acids (something like 45%). Again,

this is all driven by the desire to have a smaller, more stable package

than whole flowers. This process succeeds with a vengeance.

Neither of the lines was running. They don't start running

until late September, at which time they will run around the clock,

five days a week, until April. Meanwhile, the hop brokers are

selling the premium hop flowers for whole flower brewers, sending

the not-so-pretty ones to the pellet mills, and the rest to the Extract

facility there in Yakima, a wholly owned subsidiary of SS Steiner.

The extract facility uses two operations, one CO2 extraction, the

other a liquid CO2 extraction (don't ASK me how they get liquid CO2,

I thought it was only solid and gas!). About 60% of Steiner's hops go to

the pellet mill, 20% are sold as whole flower hops, and 20% go to the

extract facility.

A word about hop extract. Here's how it works. Liquid CO2 is

run through a bed of pelletized hops. It absorbs the hops oil

and resins (alpha acids are in there). Then the gas is allowed to

evaporate, and the extract is left. Steiner's Technical Director,

Darwin E. Davidson, claims that this process 'gives a true flavor.' Now:

extracts CAN be split down further to pure alpha acids, hops oil,

and beta acids. But the oils' flavor is changed by the process.

The extracted alphas can also be 'isomerized.' (This is what actually happens

in the kettle to alpha acids, Darwin said.) You can add the iso-alpha

acids directly to the beer for hop 'character.'

There is a further step used by Miller Brewing for hops for

their clear-bottled beers. They take the iso-alpha acids and hydrogenate

them, much like is done at refineries: they force hydrogen through

the oils at extremely high pressures. This produces rho-iso-alpha

acids, also known as tetralones. Oddly, a somewhat more complicated

process can create identical compounds from the beta acids. These

tetralones have intensified bitterness, better immunity to sunlight, and

increase foam stability and retention. Needless to say, they do not

maintain the flavor of fresh hops.

Hop-picking mural on the side of the American Hop Museum.

At Long Last: We Drink Beer!

After we left the pelletizing facility we tasted Grant's new

seasonal beers. What we got first was the Springfest Ale. This booger is

hopped with Willamette and Cascades, 5.8%ABV, 15P OG, 3.3P FG, 25-30 IBU.

We got it unfiltered, and without the dry-hopping. We liked it just

fine. The relative lack of hop aroma was more than made up for by

the 'cask' quality of the lively yeastiness. This was a good fruity

beer, too: Bert uses the same ale yeast for everything he brews

(except the hefe, which is "dusted" with Weihenstephan yeast

in the post-fermentation). The story is that when Bert was doing

research for Canadian Breweries, he took the opportunity to screen

400 different strains of yeast. He chose this one, and kept it against

the day he would be brewing himself.

Then we tried the Summer Ale, dry-hopped with Chinook. This

was surprisingly nice in the hop aroma department, I hadn't really

thought of Chinook as an aroma hop. It was otherwise uninspiring, my

least favorite of the bunch. Then we got the Fresh Hop Ale. 5.2%

ABV, somewhere around 25-30 IBU (it varied from batch to batch), and

purely hopped with Cascades, along with that late addition of fresh

Cascades. Now, it was GOOD, don't get me wrong. I would drink lots and

lots of it. But for a beer called "Fresh Hop Ale," I expect

it to be pretty damn hoppy. If 'hop' is in the name, you know. The

green hop character was subtle; there, but subtle. If I had not known

what was going on, I would have written it off as a yeast effect.

My favorite was the Mt. Hood-hopped (really like that hop!)

Winter Ale, with 6.0%ABV, 16P OG, 3.5P FG, 30 IBU, and honey, wheat, and

roasted barley. This was a delicious, chewy beer that was still very

drinkable. After all, 6.0% ain't HUGE for a winter beer. I'd love some

of this come December.

Then we had some free time, and met back at the brewpub for

dinner. Dinner was not that great. The salad was uninspired, there was a

neat little green bean and purple onion in vinaigrette with goat cheese

thing, but the 'steak lasagna' was poorly planned and more poorly

executed. The appetizers were GREAT, though: Stilton cheese and

french toast rounds with fresh grapes, real nachos, and hummus and

pita wedges. Likewise the beer: I dug deep into the IPA and Imperial

Stout and rarely came up for air!

The last course of the dinner was back at the hotel lounge:

cigars. After a bad experience with Ben's Don Tomas cigars

the night before I stuck to cadging Hoyo de Monterrey's from Alan

Moen. Unfortunately, it was bad comedy night in the lounge: the guys on

stage sucked EVERY bit as much as you would guess comedians in

Yakima would. The one guy had a whole routine of Wyoming jokes (which

I'm sure became Montana jokes when he was in Cheyenne) which would make

you cry from pity. So we left. We went to a sports bar which had Alaskan

Amber and three taps of Bert's beers (my kind of sports bar!), then

an Irish pub which did not serve Guinness (NOT my kind of

Irish pub!). Then it was home for sleep, and sleep I did.

Day 3: Ben Puts Us To Work

On the last day... We were rolled out of the sack for another

delicious breakfast (one nice thing about farm-country restaurants: they

sure-GOD know how to make breakfast!), and were herded onto the bus. Out

we went to Rick Van Horn's hopyard, where Ben had located some Cascades

that were just being harvested that morning. We sat around in the bus

while Ben apparently tried to make small talk with the migrant

workers (we should have let Chris Brooks go out and talk to them,

he had gotten fairly twisted the night before and insisted that

he was "Senor Lopez!" in fairly impressive Castillan

Spanish), then Van Horn showed up and yanked down three big leafy

pythons of Cascade vines for us.

We cheerfully marched them over to the back of the bus,

stuffed them in, and headed back to the brewery. We were there in 20

minutes, and Ben handed out gloves and nylon bags. We set to work

picking hops. When we had one nylon bag two-thirds full, Ben said we

could stop, because "the group we had last week told me to get

bent long before they got this far!" So, would that make us good

sports, or suckers? Doesn't matter, cuz we then got to drink Fresh

Hop Ale, so we didn't care. We quenched our thirsts, then set out on

brewery tours.

It was a brewery tour. You've all been on them. There was a

kegging room, a coldroom (a big one: the one before this one had

collapsed in an unusually heavy snowfall the winter before, ruining the

entire store of beer. Grant's started from zero and brewed around the

clock for a while.), a bottling line, yada yada yada. Unusual stuff: a

real copper brewkettle (for heat properties and the unsure chemical

properties), a gravity brewhouse (the kettle was way up in the tower,

pretty cool, really), and Bert's yeast strain.

Then we talked to Bert. Bert started working in

breweries at age 16, in 1945. Things were different then:

"Budweiser was around 20-22 IBU, about 15-20% rice."

(Ben jumped in at this point, chiding Bert for saying things

that "of course we can't really say for sure, since we're

not Anheuser-Busch!" Marketing weasel...) Bert made

a telling point, talking about his days at Canadian Brewing. The

beer was being made lighter and lighter, supposedly to

appeal to the market's changing tastes. "Most of these

decisions were made by people who didn't drink beer. We'd

have the Christmas party and there'd be two bars. At one end

would be the bar with beer, and all the brewers would be down

there. At the other end would be the bar with the liquor, and

that's where all the marketing people would be."

Then we talked to Bert. Bert started working in

breweries at age 16, in 1945. Things were different then:

"Budweiser was around 20-22 IBU, about 15-20% rice."

(Ben jumped in at this point, chiding Bert for saying things

that "of course we can't really say for sure, since we're

not Anheuser-Busch!" Marketing weasel...) Bert made

a telling point, talking about his days at Canadian Brewing. The

beer was being made lighter and lighter, supposedly to

appeal to the market's changing tastes. "Most of these

decisions were made by people who didn't drink beer. We'd

have the Christmas party and there'd be two bars. At one end

would be the bar with beer, and all the brewers would be down

there. At the other end would be the bar with the liquor, and

that's where all the marketing people would be."

Bert also said that German brewers' reverence of the

Reinheitsgebot is "phony. I go over there to tour, and

they have chemicals and additives sitting in their warehouses.

But they tell me 'Oh, that's only for our export beers.' As if

that made it better!" He said that Stimson Lane's wine

distribution channels have insulated Grant's from the effects of

A-B's '100% share of mind' campaign, which has crippled so many

micros' distribution.

It was an interesting talk, but over far too soon. We had

to run for the airport for an 11:20 flight out. We thanked Bert,

and Ben, and flew away. As we lifted out of SeaTac Airport I had

a great view of Mt. Rainier, what was left of Mt. St. Helens,

and Mt. Hood. It was a nice way to end a good trip. After

an uneventful flight to Dulles, I spent 45 minutes talking

writer trash with Peter Terhune, then flew home.